It all began in February of 1891 when advertisements for a new parlor board game began to appear in

newspapers around the country. It was called "The Talking Board" and it was presented as a magical device that

would answer whatever questions were posed to it about the past, present and future with remarkable accuracy. It

would be a mystical link to the unknown that could be brought into the comfort and privacy of your own home for

the princely sum of $1.50.

The board that was produced back then was essentially the same as sold in toy and novelty stores today,

displaying the numbers 0-9, the letters of the alphabet and the words "yes", "no" and "goodbye". The layout has

not deviated much over the years with the letters arranged in a semi-circle, the numbers in a row underneath that,

the words "yes" and "no" in the uppermost corners and "goodbye" at the bottom. The first boards and planchettes

were made of wood, but in the modern mode of mass production, affordability and profit margin, contemporary

boards are often made of cardboard with a plastic planchette.

The triangular or heart-shaped planchette (French for "little plank") that accompanies the game is used as a

vehicle to maneuver around the board. The designed method of operation is for one or more people to place their

fingers on the planchette, ask a question and without any human manipulation, observe the planchette move of its

own volition from letter to letter (or number) spelling out a word, name, number or date or to the yes/no areas in

response to a simpler query.

The First Patented Board Typical Board Today

The board was reported to have been tested and proven to work as advertised inside a US Patent Office before

the copyright was issued. One can only speculate what the testing entailed and what enigmatic details were

revealed to those present on that fateful day, but what are the origins of this object and what served as the

catalyst for its creation?

From the mid to late 19th and early 20th centuries, what was referred to as The Spiritualist Movement had its

origins in the western and central regions of New York state. By the 1840s, this was where free thinkers and those

disillusioned with the constraints of their religious upbringings relocated to bond with like-minded people in

establishing new religious sects. This era is commonly known as the Second Great Awakening, a Protestant

movement that in essence was an antithesis to the escalating application of science and rational thinking in

ascertaining mankind's origins and its greater purpose. Like the Millerism and Mormonism sects that were formed

in the same region, Spiritualism quickly gained followers. It is based on the belief that spirits of the deceased have

the ability and desire to communicate with the living. The afterlife is considered a place of continued evolution and

that spirits become enlightened and more advanced than the living and can provide guidance and counsel in

moral, ethical and spiritual matters.

In 1848, Spiritualism found its springboard with the discovery of and subsequent celebrity bestowed upon the

Fox sisters of Hydesville, NY. In March of that year, Margareta "Maggie " Fox and her 11-year-old sister Kate

excitedly insisted a neighbor come into their home to bear witness to a strange phenomena that took place each

night at bedtime. They claimed to be in communication with a willing, intelligent entity who responded to their

questions with a series of knocks or raps on the walls and furniture. When it came time for a demonstration to

prove the veracity of this bizarre claim, it appeared to all present (and subsequently all who would pay for the

privilege of marveling at this phenomenon) that the young girls were telling the truth. It was then, that Spiritualism

as a recognized religious movement truly took flight.

Eventually Maggie, under some duress and by then estranged from her sister Kate and an older sibling Leah,

renounced their act as nothing more than a "common deception".

“My sister Katie and myself were very young children when this horrible deception began,” Maggie said. “At

night when we went to bed, we used to tie an apple on a string and move the string up and down, causing the

apple to bump on the floor, or we would drop the apple on the floor, making a strange noise every time it would

rebound.” The sisters graduated from apple dropping to manipulating their knuckles, joints and toes to make

rapping sounds. “A great many people when they hear the rapping imagine at once that the spirits are touching

them,” she explained. “It is a very common delusion. Some very wealthy people came to see me some years ago

when I lived in Forty-second Street and I did some rappings for them. I made the spirit rap on the chair and one of

the ladies cried out: ‘I feel the spirit tapping me on the shoulder.’ Of course that was pure imagination.”

To illustrate her point, she offered a public demonstration, removing her shoe and placing her right foot upon a

wooden stool. The room fell silent and still, and all present bore witness to a number of short little raps. “There

stood a black-robed, sharp-faced widow,” the New York Herald reported, “working her big toe and solemnly

declaring that it was in this way she created the excitement that has driven so many persons to suicide or insanity.

One moment it was ludicrous, the next it was weird.” Maggie insisted that her sister Leah knew that the rappings

were fake all along and greedily exploited her younger sisters. Before exiting the stage she thanked God that she

was able to expose Spiritualism. This obviously did not sit well with devout Spiritualists.

Oddly, a year later, she recanted her “expose” by saying she was compelled by her “spirit guide” to do so and

that in fact, everything the Fox sisters came to be known for was totally legitimate. This prompted even more

anger from Spiritualists who denounced her as someone who turned against the movement only for personal gain

and attention. Eventually Maggie would for all intents and purposes, drink herself to death by 1893.

The Fox sisters - Maggie, Katie and Leah

Fueled by the exploits of the Fox sisters, Spiritualists jumped into the spirit communication pool with both feet.

Rappings and knocking sessions eventually evolved into practices such as séances, automatic writing and table

tipping. Social gatherings were held that revolved around these activities. (By the early 20th century, Spiritualists

numbered over 8 million in the U.S. alone.) The very possibility of contacting the dead filled a very emotional and

personal void in people's lives in a day and age where the average lifespan was less than 50 years and medical

practices were still evolving. It was also a time of war and the bloodiest conflict in our nation's history.

The loss of sons, brothers, husbands and fiancées to the Civil War was for most, traumatic and emotionally

devastating. Males lost their lives at tragically young ages, many struck down before adulthood had even begun.

For their survivors, any existence of a method or support system that offered communication with lost loved ones

was a siren call that prevailed over any sense of rationality. The prospect of communication with the spirit realm

even reached the highest levels of government as First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln was known to host séances inside

the White House in an attempt to contact her 11-year-old son William Wallace "Willie" Lincoln who succumbed to

typhoid fever in 1862. There are also rumors - unsubstantiated - that even President Lincoln consulted mediums

and clairvoyants to glean some spiritual "insight" when faced with crucial executive decisions, especially during

the War Between The States. It was in this period that Spiritualism and access to those who claimed to facilitate

this process saw its largest spike in advocacy.

Before the more nefarious among them indulged themselves in Spiritualism (and people's wallets), the public

went about the business of contacting the dead with sincerity and good faith. The problem was, the departed often

seemed somewhat reluctant to respond and patience be damned, the whole process was getting pretty tedious.

The world had entered into a new age of discovery and because long distance communication was now a reality,

surely there must be a more expedient method in which to send and receive messages to the other side. The

occasional bang on a wall or floor was all well and good, but somebody had to put their minds to this issue.

So let's stop here for the sake of clarity. At this point in time there were millions of practicing Spiritualists in the

U.S. Spirit communication had taken the country by storm and where there are millions in need, there is a

demand. And where there is a demand, there are capitalists more than willing to meet that demand. A device was

needed to bring instant gratification at relatively small manufacturing costs. Electricity wasn't yet a viable option,

but something else might be.

By 1886, wire services were carrying stories of a new craze that was all the rage in Spiritualist assemblies in

the state of Ohio. It was called The Talking Board. The original prototypes looked suspiciously like what would

eventually be manufactured by the Kennard Novelty Company in 1892. It should be noted that none of the original

investors were Spiritualists or for all we know, even accepted the idea of speaking to the dead, but they were

shrewd businessmen and they knew an opportunity when they saw one.

"One gentleman of my acquaintance told me that he got a communication about a title to some property from his

dead brother, which was of great value to him. It is curious, according to those who have worked most with the

new mystery, that while two persons are holding the table a third person, sitting in the same room some distance

away, may ask the questions without even speaking them aloud, and the answers will show they are intended for

him. Again, answers will be returned to the inquiries of one of the persons operating when the other can get no

answers at all. In Youngstown, Canton, Warren, Tiffin, Mansfield, Akron, Elyria, and a number of other places in

Ohio I heard that there was a perfect craze over the new planchette. Its use and operation have taken the place of

card parties. Attempts are made to verify statements that are made about living persons, and in some instances

they have succeeded so well as to make the inquirers still more awe-stricken."—New York Tribune.

— Carrier Dove (Oakland) July, 1886: 171. Reprinted from the New York Daily Tribune, March 28, 1886: page 9,

column 6. "The New 'Planchette.' A Mysterious Talking Board and Table Over Which Northern Ohio Is Agitated."

The Ouija board (more on the origins of the name later) was intended to be nothing more than the latest

addition to the spiritual toolbox. It was not specifically designed to be a conduit to the afterlife or a portal to

potential torment and misery as much as it was an amusement that would generate profits. The first boards were

the brainchild of the aforementioned Kennard Novelty Company of Baltimore, Maryland. Charles Kennard had a

failing fertilizer business housed in a building that was repurposed as their corporate headquarters. He and his

partner William Maupin were granted a patent for the invention with Col. Washington Bowie putting up most of the

cash for its initial production. Harry Wells Rusk was named president (his brother Jefferson would be the lawyer

involved in the patent appeal) and on February 3, 1891, the company was officially formed.

Eventually their thriving business expanded and a second factory was opened in Baltimore to satisfy the

demand for this new phenomenon. By this time, there was also a great deal of internal turmoil growing inside the

company (mainly a dispute over the distribution of growing profits) and as the result, by 1893 Kennard and the

other partners had been ousted by Bowie and Rusk and a branch factory was opened in Chicago, Ill. A young,

industrious man who was a favorite of Bowie and Rusk named William Fuld was pegged to head the company and

it was renamed Ouija Novelty Company to reflect the popularity of its singular commodity.

Almost predictably, corporate intrigue found its way into the picture as the original head honcho, Charles

Kennard, purchased the eventually-defunct building in Chicago and created the Northwestern Toy and

Manufacturing Company of Chicago, Illinois. There he produced the "Volo" board as a direct competitor to the now

wildly popular Ouija. Although the board's design shared some aesthetic characteristics with its more popular

predecessor, its layout (probably to avoid legal infringements) displayed its own unique look.

The Volo Board

To no one's surprise, the Ouija Novelty Company launched a preemptive legal strike against this interloper and

in less than three months, manufacture of the Volo board ceased. To rub salt in Kennard's wounds, they acquired

the rights to the Volo board as part of the settlement and printed a copy of that board on the back of the Ouija.

Essentially customers now received two boards for the price of one.

There were others who attempted to jump on the talking board bandwagon such as the W.S. Reed Toy

Company of Leominster, Ma. who designed the "Espirito Talking Board" in 1892. There is actually some debate

regarding the Reed Toy Co. as to whether or not it was they and not the Kennard Company who developed the

actual prototype. To wit:

(Regarding the development of a “new product” developed by the Reed Company:) "Upon the four corners of the

board are respectively "Yes," "No," "Good-by" and "Good-day," while the alphabet occupies the centre of the

board. A miniature standard, which rests upon four legs, stand upon the "witch board," upon which the hands are

placed, and then the spirits begin their work. Should an answer be "Yes" or "No," the small table will travel to the

respective corner, et cetera. Communications are spelled out by the diminutive table resting over such letters as

may be wanted to spell out the message”.—Boston Globe June 5, 1886

Alas, consumers deemed the Espirito inferior to the "real article" and the company ceased production a mere

four months after it began. Undeterred, Kennard again jumped into the fray by establishing the American Toy

Company in 1897 which was located right next to the original Kennard Novelty Company in Baltimore. The new

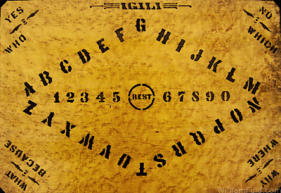

board was christened "Igili, The Marvelous Talking Board". By 1899, Kennard's fourth attempt at the talking board

business mirrored that of the first three. Epic failure.

"Igili, The Marvelous Talking Board"

There were other attempts to tap into the talking board market like the "Nirvana Talking Board" (in the interest

of clarity, it predated the Seattle grunge band by some 90 years) which was offered up by the regrettably named

Swastika Manufacturing Company. By this time there was no doubt that nothing said "communing with spirits" like

the Ouija.

Eventually, William Fuld and his brother Isaac would take over the manufacturing of the Ouija board while Col.

Bowie and Harry Rusk enjoyed the benefits of retirement and residuals. In time, William and Isaac would

experience a falling out, leaving William with the exclusive rights to manufacture the Ouija Board and by 1919 he

became sole owner of the company. He went on to patent many novelties beyond the board and held 33 different

patents and trademarks. In subsequent years, he would also have to deflect and endure continuing controversy as

the deposed partners maintained their struggle for residuals and credit for the invention of the board.

William Fuld met a tragic end when he died from injuries suffered in a fall from the roof of his factory. While

overseeing the replacement of a flagpole, a support gave way and he plummeted three stories. While he lay on

his deathbed, he implored that his children never sell the Ouija board company. The business remained in the

family, run by his son William A. Fuld, until his own age and health issues led to the sale of the business and the

rights to the Ouija board to Parker Brothers in 1966 - on the 39th anniversary of their father's death.

William Fuld

Finally we get to the burning question. We have the talking board being utilized by Spiritualists in a camp in

Ohio, so where did they get the name "Ouija" from? Many people have accepted - incorrectly - that it is a

combination of the French word for "yes", (oui) and the German version, (ja). Robert Murch, one of the leading

Ouija researchers in the country and the closest thing to an expert on the subject claims that according to letters

written by the founders, Elijah Bond, one of the original partners in the Kennard group and the man who actually

received the patent for the board, had a sister-in-law named Helen Peters. Helen was a spirit medium according to

Bond and while sitting around a table thinking of a name for the new product, they decided to ask the board to

name itself. The name "Ouija" was spelled out and the question of what it meant was then asked. The words

"Good luck" were then spelled out.

It has also been said that "ouija" is an Egyptian word (no doubt adding to its air of mystery). But before we get

too excited about all this foreordination, Peters admitted she was wearing a locket that bore the picture of a

woman that appeared to have the name "Ouija" over her head. Murch asserts it is a distinct possibility that the

woman pictured in the locket was author Maria Louise Ramé who wrote under the pseudonym Ouida. Peters had

a great fondness for her work, so perhaps that name was misread or mispronounced by her or someone else

present.

Now this is where the story takes a weirder turn. The tale goes that a demonstration of the board was

necessary in order to prove its authenticity and to secure the patent. The patent clerk asked Bond and Peters

(who was attending at her brother-in-law's request) to have the board spell out his name. The premise being that

neither Bond or Peters knew who he was at that point in time and if the board proved correct, the patent would be

granted. They sat down at the board and the planchette indeed spelled out the astonished clerk's name. Patent

granted. (In the spirit of full disclosure it must be noted that Bond was a patent lawyer and perhaps already knew

the man's name.)

The gambit paid off in a big way as the board game became an overnight success story. To meet the growing

demand, additional factories were opened in New York and London and business was booming. At the heart of the

Ouija phenomenon the key question remained, "How does it work?" The manufacturers, perhaps intentionally

creating an air of mystery and ambiguity, never properly answered that query and in fact went out of their way not

to tender an explanation. Or, more likely, because they had no idea or interest in really knowing. If sales were

good and cash was flowing in, then leave others to their own devices to explain the mysterious ways and

measures of the darned thing.

By the early 1900s, the Ouija craze was at its peak throughout the country. For many, it developed into a very

mainstream and acceptable way to spend one's spare time. For others, it bordered on an obsession as more

pervasive things tend to do in our popular culture.

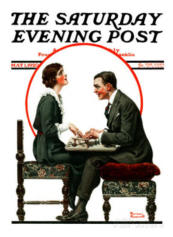

Even Norman Rockwell had a take on the phenomenon

Along with the mostly positive reviews of the game, there was also the occasional bizarre story associated with

its use, some of which found their way into national publications. These

included the Chicago woman who stored her deceased mother's body in

the house for 15 days after her death before burying her in the backyard.

Before being committed for psychiatric evaluation, she explained to

authorities she was merely carrying out the instructions relayed to her by

spirits she had contacted via the Ouija board. Not only was the board an

accomplice to committing crimes, it was also occasionally consulted in

attempts to solve them.

In perhaps the most peculiar instance of obsession, Mrs. Helen Dow

Peck of Bethel, CT. left the sum of $152,000 in her Last Will and

Testament to one John Gale Forbes who - apparently like Mrs. Peck - was

neither of sound mind or body as he was an entity who contacted Mrs.

Peck through her Ouija board.

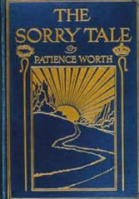

These were not just isolated cases involving a certain fringe element of society, either. A housewife from St.

Louis, Missouri named Pearl Curran (above right.) who otherwise claimed to have no particular interest in the

occult, began to dabble with the board over afternoon tea with her mother and a neighbor. One day to their

astonishment, the board spelled out the following message from someone who identified themselves as a 17th

century female. This was the initial greeting:

"Many moons ago I lived. Again I come. Patience Worth is my name. Wait, I would speak with thee. If thou shalt

live, then so shall I. I make my bread at thy hearth. Good friends, let us be merrie. The time for work is past. Let

the tabby drowse and blink her wisdom to the firelog."

This was particularly shocking because previous sessions had yielded nothing but nonsensical and random

groupings of letters. Over time, Patience would go on to share her background with Pearl and claimed she was

born in England and migrated to America where she was eventually killed by Native Americans in a raid on the

island of Nantucket. Soon Pearl asserted she no longer required the board as a conduit as the messages from

Patience were simply channeled directly through her. Many of these sessions produced poems and entire plays

that were transcribed by Pearl's obliging husband John who would write all of it down as Pearl dictated to him.

One of the more unusual and intriguing elements of this collaboration were specific words, places, names and

phraseology from another era which Pearl - presumably - should not have been aware of. The end of this mystical

literary venture coincided with Pearl's pregnancy at the age of 39 and the passing of her husband and mother. Her

"contact" with Patience began to wane over this period until it ended entirely.

Now, this all took place in 1916 and while it is a gripping tale considering Mrs. Curran's muse was the spirit of a

woman who lived in the 17th century and because her own educational background casted reasonable doubt she

had any knowledge of an archaic language, there may be more here than meets the eye. For example, the name

Patience Worth was a familiar one, as she was a character in a novel written by Mary Johnston titled, To Have and

To Hold based on Colonial life published in 1900. The phrase "many moons ago" in her initial message is distinctly

Native American and most likely not a phrase commonly used by anyone in 17th century England. The absence of

any similar colloquialisms in subsequent messages speaks to some level of inconsistency. While perhaps not

completely relevant to any arguments against her experience, Pearl did have a mental breakdown at age 13 and

in the estimation of some family members, was something of a hypochondriac. She also briefly lived with an uncle

in Chicago who ran a Spiritualist church out of a storefront, so while she claimed to have no particular interest in

the supernatural, she nonetheless had some exposure to it at an early age and the idea of channeling or spirit

communication may not have been totally foreign to her. The mystery that remains is whether Pearl Curran was

indeed in spirit contact with a woman from the 1600s named Patience or she perpetuated a hoax testing everyone

else’s. It’s also possible this was not intended to be a long-term hoax planned as a means to fame and fortune

(although she did eventually take to the stage to "perform" for money), but an unconventional approach to

expressing herself on an intellectual level that simply spiraled out of control.

Interestingly, the "neighbor" mentioned in regards to

Pearl Curran's first afternoon Ouija sessions was a

woman named Emily Grant Hutchings who is generally

credited with introducing Pearl to the wonders of the

Ouija. One year after Pearl's literary debut, Hutchings

also published a book titled, Jap Herron that she claimed

was co-authored by Samuel Clements, aka Mark Twain.

The more bizarre component to her assertion is the fact

that Clements had passed away seven years earlier in

1910 and as Patience Worth did with Pearl Curran, his

collaboration with a living co-writer was facilitated via

these afternoon sessions with the Ouija board.

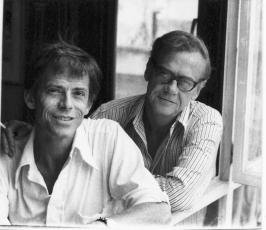

Perhaps the most celebrated piece of channeled

literature is the epic poem, The Changing Light at

Sandover by James Merrill. The 560-page sonnet was the result of a twenty-year transcription of messages

received through a Ouija board by Merrill and his partner, David Jackson. The massive work is actually a

compilation, with 1976's Book of Ephriam (which appeared in the collection Divine Comedies that won the Pulitzer

Prize for poetry in 1977), Mirabell: Books of Number (National Book Award for Poetry) in 1978 and Scripts for the

Pageant in 1980 being combined into one volume. Sandover would go on to win the National Book Critics Circle

Award in 1983. Merrill actually acknowledges his muses in the credits: Ephraim, said to be a first century Jew

and; Mirabell, a ouija board guide.

So obviously while there were some strange, eccentric, and, in some

cases, commercially and critically acclaimed alliances formed using the Ouija

board, for most of the population the game remained a favorable time-killer

and the preferred method of foretelling romantic involvements of teen-aged

girls on sleepovers. Despite some rare instances of emotionally and

psychologically fragile souls being "compelled" to perform unthinkable and

absurd acts, it was generally regarded as a harmless diversion. For the more

spiritually devoted, the board was considered an invaluable link to the afterlife

and any and all replies from The Great Beyond were to be taken very

seriously and treated with the utmost respect and

caution. Regardless of what side of the fence you

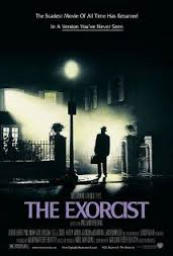

were on, the Ouija lived a fairly benign existence. This all changed (as the entire

paranormal paradigm would) with the release of a motion picture in 1973 titled, The

Exorcist.

It wasn't until five years after its release that I finally acquiesced - at the urging of my

then-girlfriend and her devoutly religious mother (this didn’t end well for her) - to seeing

the movie. Even as a 22-year-old strapping young man trying his best during the film to

convey an air of indifference to both impress and calm his girl and placate her

increasingly-hysterical mother, the film was as truly disturbing to me as it was for millions

of others. (Mission accomplished, Kubrick.) As a plot device, it plays on the deepest and

most elemental fears in many of us. Putting the spectacle of its graphic violence and

language aside, at its foundation its effect on myself boiled down to two basic elements:

(1) Does this really happen? and; (2) Could it happen to me? Exacerbating my dilemma of

faith was the knowledge that the movie was based on a "true incident" (it's generally

accepted that the “Roland Doe” case involving a young boy in St. Louis formed its basis) and the notion that most

major religions accept possession and the rite of exorcism in some form as a reality, albeit rare.

For the unfamiliar, the film’s main character is young Regan McNeil (played by then 12-year-old Linda Blair)

who portrays an innocent child who becomes possessed by a demon. Her facial features become grotesquely

distorted and her body ravaged by the intruder. Early in the film and prior to her ordeal, she reveals to her mother

Chris that she has been fooling around with (plot device) a Ouija board. She further claims she had summoned an

entity she calls "Captain Howdy". For many movie-goers it was their first exposure to the notion that a demonic

entity can masquerade as something seemingly harmless and benevolent to ingratiate themselves with their target

and ultimately gain access to their soul. It was a seminal point in popular culture that the Ouija board went from an

object of humor, entertainment and pseudo-mystery to something to be feared and avoided lest one tempt the

fates and open a portal to Hell.

The entertainment industry, seeing a hot commodity capable of generating millions of dollars from consumers

eager for more, launched a spate of imitators which sprung up almost overnight. Movies like Alison's Birthday, The

Devil's Gift, Spookies and the best of the bad, Witchboard, feasted on the burgeoning and highly-manufactured

uneasiness - bordering on abject fear - centered around the hazards of the Ouija board. Soon another wave of

movies featuring Satan and his minions popped up in an attempt to take advantage of the Exorcist's wild success.

The Omen and The Amityville Horror met with decent reviews, but the list is far longer and for the most part, quite

undistinguished. Film studio executives who had already recognized the power of movies to influence popular

culture through the attitudes and emotions of the American public, were trying to catch the same lightening in a

bottle The Exorcist had generated amid dreams of "franchise" films with interminable, yet profitable sequels

waiting in the wings. The kind of ancillary publicity The Exorcist had generated with religious groups decrying its

very existence could not have been totally foreseen (even employing a Ouija board), but controversy served as an

even greater catalyst for people to pay good money to take the dare and be scared out of their wits. People don't

mind being artificially frightened, especially if they know after two hours of shocks and startles they can safely

return home none the worse for wear. Physically, anyway.

Because of the growing association between the Ouija board and the forces of evil (aided in no small part by

the media portrayal of that unholy partnership to the multitudes), fundamentalist religious groups continued to take

up the mantle of morality and decency by means of public protest, condemnation and boycott of theaters indulging

in such blasphemy. There were public burnings of boards and the citing of scripture prohibiting communication

with the spirit world, effectively issuing a denouncement of any attempt to do so lest one tempt fate and annoy

God by summoning The Dark Lord himself. As we have since become increasingly aware of in this new era of

identity politics, public protest is also a great way to draw some attention to yourself and your cause. Back then,

however...these hard-right folks were dead serious! For film studios, they literally couldn’t pay for that kind of free

publicity.

In a short span of time, this simple amalgamation of plastic, cardboard and ink had become an unwelcome

interloper and had to be dealt with in the strongest terms possible. Naturally, there were some rolling of eyes and

shaking of heads by the more reasoned who understood that the game had been around for about 100 years

before The Exorcist was released. For many others, because of the current notoriety and negative attention

surrounding the game, it was as if the genie had escaped its bottle and had to be put back. The delicious irony

was that religious opponents had been just as powerfully manipulated by fictional portrayals as were the

unwashed masses they now swore to protect and enlighten. The spiritual relevance, entertainment value and

casual curiosity once linked to this 19th century parlor game had been replaced by a preternatural cocktail of

equal parts inappropriateness and apprehension with a dash of mass hysteria thrown in. The Hasbro Toy

Company of Pawtucket, R.I. would eventually acquire Parker Brothers in 1991 and sales of the board remained

respectable, but the grounds for purchase now reflected more nefarious and superficially dangerous elements.

In contemporary times, the Ouija board has seen a resurrection of sorts. The world finds itself in yet another

cycle of turmoil and uncertainty and interest in the paranormal has reemerged again in popular culture. Both

network and cable television as well as movie studios feed it to a public with a voracious appetite for all things

supernatural. News programs and even normally haute magazines and newspapers will run the occasional semi-

evenhanded feature on some paranormal sighting or strange experience that formerly was relegated to the

Halloween editions or the office shredder. In the business of giving the masses what they want, the sheer number

of TV shows dealing with the "reality" of the paranormal and those who pursue it is astounding as even

educationally-based networks tapped into "The Next Big Thing". The Ouija board - used often as a plot device -

made regular appearances as a co-star or in cameo roles. Never one to be left behind, even the personal

communications industry developed a Ouija board app for smart phones for people seeking a direct line to the

afterlife.

The Ouija board exerts an odd hold on the emotions and beliefs of many Americans and people all over the

world. It also creates a sort of "home version" of what people otherwise pay goodly sums of money to divine with

the assistance of spirit mediums. Family and friends can sit around the board and ask it typical questions one

would in a desire to foresee the future or gain insight into a particularly vexing problem. (Ed: It should come as no

surprise that in the beginning, those most adversely affected by this cultural phenomenon were the spirit mediums

themselves, who foresaw their roles in this passion play greatly diminished.) There is also a certain element of

peril involved when people venture into the Great Unknown. This provides the type of adrenaline rush or "cheap

thrill" that so many people crave and - like the stylized horror movies that one can find on any number of cable

channels, DVDs or pay-per-view outlets - it can take place in the comfort and privacy of one's own home. It also

speaks to a large extent of the desire to believe in some higher power, something greater than us that controls our

fates and offers up some type of solace in knowing there may be more to life beyond this mortal coil. A place

where those who pass over can still stop by to send their regards and respond to our inquiries.

It's interesting to note that wide-spread interest in the paranormal is very much a cyclical thing and this has

been borne out through history. In times of great political, financial or social upheaval, people have trended toward

the spiritual. This is especially true in times of military conflict. The Civil War, the World Wars, the Vietnam War

and the current threat of international and domestic terrorism all coincide with spikes in a renewed interest in the

spiritual and supernatural. In 1944, a single New York department store sold over 50,000 boards at a time when

disposable income was scarce. The Great Depression saw new factories opened to meet the burgeoning demand

for the Ouija. In 1967, one year after Parker Brothers purchased the rights to the game, sales exceeded 2 million,

outselling the preeminent board game of our time - Monopoly. Was it sheer coincidence that this was the year that

saw the first movements of a burgeoning counter-culture, the escalation of troops in Vietnam and violence

resulting from the boiling-over of racial tensions? Perhaps the senseless and heartbreaking loss of lives, financial

distress and the plight of the disenfranchised and socially disconnected are the most prominent factors that

contribute to the turn toward the otherworldly.

THE OUIJA BOARD - DEMYSTIFIED

BY: KEN DECOSTA